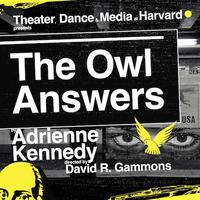

The Owl Answers was written during foment in the 1960s. The assistant director on the new TDM production has found resonance for her understanding of history, theater and identity.

The Owl Answers was written during foment in the 1960s. The assistant director on the new TDM production has found resonance for her understanding of history, theater and identity.

By Aislinn Brophy '17

Guest Blogger

Aislinn Brophy is a Boston-area actress, playwright and director who works primarily to create theater exploring the intersections of identities onstage. She is particularly interested in the ways in which race and gender inform both how we see ourselves and how others perceive us. In May, she graduated from Harvard with a degree in Theater, Dance & Media after writing and directing her original work Dryside. She is the assistant director on Theater, Dance & Media's production of The Owl Answers, which runs Oct. 13-21 at Farkas Hall.

When I was first asked to assistant direct The Owl Answers this summer, I knew little about the play. The Theater, Dance & Media field of concentration had announced that it would be the fall show as I was beginning the process of fading away from Harvard undergraduate life in my final semester of senior year. I hadn’t paid much attention to the announcement, as I was turning my focus towards the process of attempting to sort out what I would do after graduation.

Had I been paying more attention last spring, I likely would have been disgruntled that a play so firmly within my interests was being done after my graduation. Written by Adrienne Kennedy in the 1960s as a part of the Black Arts Movement, the play depicts a mixed-race, African American woman named Clara attempting to construct a sense of

The historical resonances and connections, however, are not only limited to the text of the play. They continue even into the process of creating this project. For instance, Kennedy, is a dear friend of David Gammons, the director. They met in the early 1990s when he took her playwriting course an undergrad at Harvard, which makes the return of her work to the stage at Harvard with him at the helm seem as though things have come full circle. In rehearsal, we also had the pleasure of speaking with avant-garde theater artist Robbie McCauley, who has acted in and directed Kennedy plays since the late 1960s.

There is something magical about listening to someone speak about the 1960s who truly lived through them. McCauley told us stories about the experience of being in the cast of Kennedy’s A Beast’s Story, which was presented nightly with The Owl Answers as a part of a double-bill entitled Cities in Bezique. She spoke about working at the Negro Ensemble Company, a groundbreaking theater company established in the 1960s and based in New York City. Near the end of our time with her, after a cast member asked about what it was like to be a part of such a significant cultural period, McCauley spoke about the day that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. It was this weighty story that I have carried with me since I heard it, and it has brought into focus for me what feels so salient about working on The Owl Answers.

Our racial history in this country is a heavy one. It is a history that weighs on us, shaping who we are even when we are not fully aware of it. We all hold a multiplicity of identities within us – identities that jostle to be seen and heard even when they seem to be contradictory. Kennedy puts these contradictions onstage, creating something that seems just as disturbing and revelatory as I imagine it felt in the 1960s.

This is why, for me, The Owl Answers is personal. As a mixed-race, African American woman, I am currently wrestling with many of the same issues as the main character in the play. I have spent years attempting to construct an understanding of what it means to be both black and white in this country in this moment. To be clear: The Owl Answers is personal to me because American history is intensely personal. How do you construct who you are today without a sense of whom came before? And obviously, American history does not exist in a void; it is linked to the histories of other nations through struggle, cooperation and the unceasing flow of people throughout the globe. Who are we as a nation without our English ancestors? Who are we without our African ancestors? Who are we without the people who have travelled from countries across the globe as tradespeople, tourists, immigrants and slaves?

I believe that we must look back so we can truly see ourselves as we are. We must attempt to understand for ourselves where and whom we come from, and what identities we hold within ourselves. And that, at its core, is exactly what this production of The Owl Answers seeks to do.